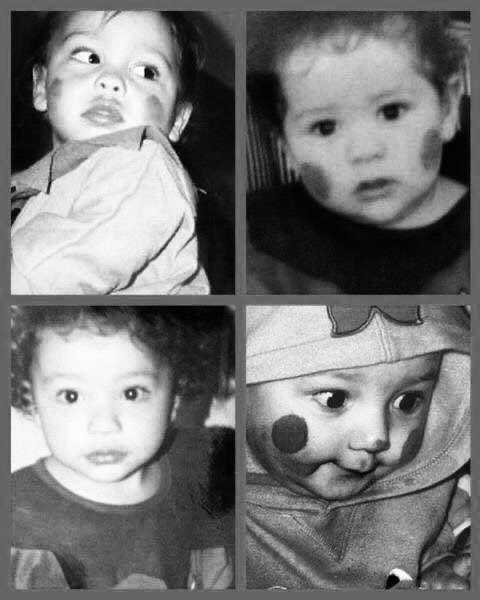

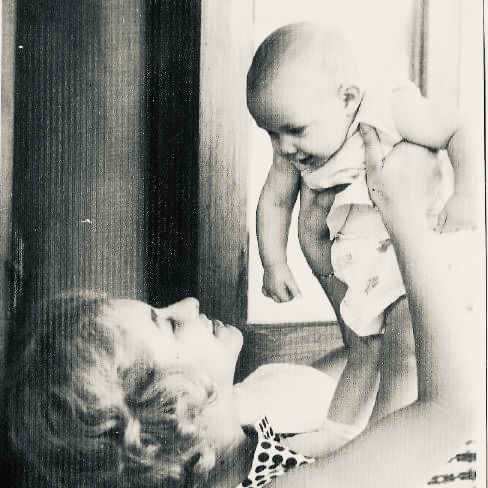

Girls are different. From boys. This is continually pointed out to me by my friends who are mothering daughters. This I already know. Awash as I am in this sea of testosterone that I live in, and drown in, the only female living with five men, believe me, I’ve noticed. I like boys. I birthed several of them, was raised in a houseful of males and have what my mother would certainly consider to be a shocking and unseemly number of sustained long term relationships with several men friends. Young and old, near and far, gay and straight, old lovers and the permanently platonic, relatives by blood or marriage; friends from work, or the theatre, or from childhood, armfuls of nephews and cousins. Boys are great fun. My husband just shakes his head, my mother just rolled her eyes and sighed, my single female friends want introductions to all the straight, eligible and unmarried ones though there are not too many of those. Men are deliciously uncomplicated once the prospect of coupling is taken out of the equation. They are not competitive, have no sub textual agendas, and are honest in the absolute. I’m a big fan of the species. But I have never before been privileged to see how they get made. I came into this family we created with all manner of knowledge about the workings of the dynamics between mothers and daughters. And having once almost been an actual girl, I knew something of how they functioned. And there were some general truths that I learned in developmental psychology texts. Girls as a rule are more precocious. They develop faster, potty train earlier, are easier to wean, are more verbal, more independent, and more emotionally savvy. I had a professor who once told me that if one first gave birth to a girl and then a boy, one would be certain that the second baby was not normal; so slow they would seem in comparison to their sister. I never got the opportunity to confirm this theory. Boys are all I’ve ever made and raised. All the above may well be true but there are other researchers who suggest that the way babies of one sex or another are socialized by their mothers exacerbates the traits they are hardwired for. Mothers for instance are found to encourage independence in girls while being solicitous of boy babies. I read something once about a study that observed mothers and babies working on a problem solving task. The mothers of girls encouraged them to keep trying hard. The mothers of boys were full of help and hints and in some cases actually finished the task for their sons. This may be the result of several forces at work: one being that perhaps the less precocious baby boys did seem to need more help. The other being that perhaps the dynamic between mothers and sons is that different. In my own experience I may be guilty of that. The over-mothering of boys. And as I write this I can almost hear the guffaws and snorts of my mommy-friends who know from experience that I am spectacularly understating my case here. I am a hands-on mama. I tend to micro-manage. I give directions in a series of distinct steps and then I repeat the directions for the sake of clarity. And then I do a follow-up to confirm that directions have been followed. I was a special education teacher for most of my adult life. I suppose some old habits die hard. I suppose also that raising a houseful of boys is not so much different from managing a classroom. And I suppose when things threaten to get chaotic I fall back on my training and enter teacher-mode. I know that my children are familiar with this posturing. I know because sometimes when I am irate and using my stern teacher-voice my children will sometimes raise their hands to speak. Then I have to remind them that this is not a classroom and that they merely need to say excuse me before making a point. But it is clear to me that I need to parent this way when they are young. Not only will they not do chores or reading or homework or practice music unless they are reminded, I have also discovered that if not specifically told to do so, three of the four will not take a shower or brush their teeth. Ever. I can’t remember a single time I ever had to be reminded about homework. And I always thought hygiene was something engaged in as a matter of course. For one’s own comfort only, even if not to avoid offending others. I recently discovered, upon cleaning the boys’ bathroom (referred to here in this house as The Swamp) that they were out of soap and shampoo and had been for days. Apparently all those days, showers had consisted of them standing under running water for a minute or two. Would I be a different mother if I were raising girls, I wonder. I would think that I would almost have to be. Boys begin by feeling extremely propiratorial about their mothers and are fiercely competitive with other sons (and with their fathers) for mother’s attention it seems. Freud’s Oedipus complex or some such force at work. Three of my four were determined to marry me when they were toddlers. It was extremely cute. Being told daily in a gushing lisp that you are beautiful is a wonderful ego boost. My sons still get into arguments about who gets to sit next to me at the dinner table or in movie theatres, although no one wants to marry me anymore. I have been replaced by Meagan Fox it seems. There is continual one-upmanship and lots of self-promotion still though (I cleaned up your car Mama, but Liam did nothing) and constant pointing out perceived acts of favoritism made all the more scathing when the perceived favorite, and this position changes daily, will stage-whisper, “that’s because she loves me most.” I once read a story about a mother of three adult sons who left a letter for each boy with her will, to be read after her death. In each letter she declared, “You were always my favorite. I always loved you best. Don’t tell your brothers.” So I know I am not alone in this. It is a myth I think, that girls are more emotional. They may be more emotionally sophisticated its true; and certainly more emotionally complex. I’ll certainly agree with that. Boys I think are more emotionally concrete and primal, but are emotional beings none the less. They frown and stamp when they are angry, belly laugh when happy, and wail and sob when they’re sad. Basic and straightforward. No sublimated grief, no tempered anger, no suppressed joy. No frustration turned inward. Some of them, I think, learn to do that later. How refreshing I think sometimes, to be a male child, and have it all be so simple. I wonder how old they will be when they stop crying when they are unhappy or grieved. That remains to be seen. Once early and middle childhood have been wrangled and survived, there is male adolescence to contend with. In my own experience, once that testosterone begins to flow in earnest, boys become protective of their mothers rather than merely territorial, and begin to have confrontations with their fathers. It seems almost evolutionary in its predictability. At least in my house. Sometimes I think that if we were a family of elk, the father of the family and the adolescent du jour would be locking antlers to assert dominance. If we were a pack of wolves they would be wrestling for the title of alpha. Of course, the father always wins. He is not bigger, probably not stronger, but has more weapons at his disposal. Like the ability to declare a moratorium on video games and spending money and a firm reminder of this will often send the baby wolf skulking to the back of the cave. I always look on at these muscle flexing confrontations with fascination. I have no brothers so I have never seen this phenomenon before up close. I am incredulous that the baby wolf will keep trying even though he must know that this is not a fight he can possibly win. Doesn’t he remember that mere weeks ago he earned three days in his room for insubordination? Doesn’t the child have ANY sense? But still, after enough time elapses, he’ll try again. It’s as predictable as the rising of the sun. And these I might add, are good children. Dutiful and loyal and have never given a moment of any real trouble. Yet when the testosterone surges, all bets are off it seems. I know nothing first hand about testosterone. Estrogen surges now, I know a thing or two about. I also was a good child. Dutiful and obedient. Loathe to anger my parents, especially my mother who was a force to be reckoned with when irate. So childhood and early adolescence in my house were marked by some relatively serene years. I did not have a traditional family when I was young and while I adored my grandfather and godfather both, I had no Electra complex – that is, no desire to marry either. I do recall though being somewhat possessive and territorial with the girlfriends of my godfather who remained single and dated. I was always warned sternly to “be nice” when a new girlfriend was introduced, but of course I never was – until, that is, the young lady and I reached an understanding. My hammock time with my godfather would be logged, whether she was spending the weekend or not, and tickle fests and talks about boats and dinosaurs were not to be butted in on. Once the understanding was reached that superbrat was there to stay, all went swimmingly. I discovered a little something about myself later though. I discovered that this seeming state of unruffled placidity existed because I had never truly been thwarted by my mother. Up to a point it seemed that everything I wanted, or desired to do, my parents were in agreement with. I sang and danced, took art lessons, and later had a group of cheerful friends, and a little later, when I was fifteen, a polite and reassuring boyfriend who always brought me home on time and made affable conversation with my parents, and who never gave them a reason to worry. And then I met Julian. And caution, veracity and duty got thrown to the wind. Along with my heart. In spite of all the reasons my mother gave for finding him unsuitable, the actual reason I believe was that Julian, at eighteen, looked, and behaved like a man. He was big and athletic and bearded and long past puberty. This was certainly no boy. He was, in my mother’s estimation, hell bent on leading me down the road to ruin; and my mother knew, as mothers always know, I was more than happy to follow him. Anywhere. And he had no interest in impressing my parents. His demeanor when in their presence was much as it always was. He had no special for-parents-only persona prepared. He had not needed one, as none of the girls he’d previously been involved with had been anyone’s cosseted little baby. In fact, when he learned of my mother’s disapproval, I think he tended to amp up his persona into something slightly outrageous. And so, my mother unwisely forbade me to see him. He could visit. But I was not allowed to leave the house with him. We could spend the evening under their watchful eye; which as you can imagine, made the road to ruin difficult to access. But my parents did not take into consideration this. I had read Romeo and Juliet. When I was nine. And had kept reading it until it made sense. I knew that lovers must sometimes risk all for the beloved. For me this was pure Capulet and Montague intrigue; and if intrigue was what was called for, I was delighted to oblige. True I had no complicit nurse, or misguided apothecary or, let’s face it, muddled and extremely irresponsible priest to help me. But I had Laura and Camille. The best and most conspiratorial friends one could ask for; who, while they were not always in agreement with my schemes, participated anyway because they loved me, or because they had read Romeo and Juliet too. Where the Julian infatuation would have died a natural death if it had not been thwarted, it continued for ages, probably because it was forbidden. I became a prodigious liar and weaver of scenarios. A brazen, bold-faced little unapologetic schemer. Exit Ophelia, stage left. Enter Jezebel. And once I’d had a taste for being defiant, it seemed, I developed a preference for it. Forever the obedient child I suddenly always bristled resentfully when told what to do. But only when the directions came from my mother. With my father, directions had the quality of gentle, benign suggestion and I was happy to comply, always. Not so with my mother; and my poor father was often reduced to the role of referee as I engaged in power struggles with her, which, like those with my wolf cubs and their father, were ultimately unwinnable. Yet, I’d keep trying – to assert my independence, to strive for autonomy, to really tick my mother off. After a summer spent on a solo trip to London and Paris when I was eighteen, where I behaved myself moderately well, I immediately announced to my mother on my return that I was a woman now, and insisted upon being treated as such. I laugh now to think of it. I was certainly no woman. But the confrontations continued until I became a woman for real and was willing to acknowledge that I did not know everything, that I in fact knew almost nothing, and finally acquired some humility and grace. And made peace with my mother. Take a final bow Jezebel. This seems to be the way of it – sometimes to greater or lesser extremes. It is the process of acquiring personhood. This questioning of everything. This bucking against the loving confines of parental love and protection. It is the process by which the adolescent tests his mettle, deconstructs, reassembles, and emerges, if all goes well, as a functional, fairly competent adult human. It was this way with me. It was thus with our first born. The message is, there is hope. Probably. It’s interesting though – living in this masculine microcosm, observing the making of men. Watching them grow strength by strength, along with their ever expanding shoulders and feet, into the men they will some day be. Asserting their independence, honing their personalities along with their skills, acting the roles of brother and son to which will some day be added those of husband and father. I watch with joy, and soft twinges of regret, as my babies begin to tower over me, express opinions about politics, or evolution, or the unfairness of our discipline in voices that are increasingly guttural and gravelly, grip my arm for emphasis with hands twice the size of my own. And I am hoping that I am giving my best to them, or that at least my best is good enough. And I am loving the ride; this raising of Cain.